The earliest dip into piano study includes many ingredients some of which are overlooked or minimized. When mentoring a young child of 6 or 7, or a beginning adult student, sensitivity to tone/touch seems very basic to making music, yet it’s underplayed. While assigning finger numbers to notes and absorbing letter names are fundamental to note reading, one can’t casually move away from an attentive listening focus on a note, or two that links directly to the tactile “feel” of its ping, or “centered” resonance. This physical fusion with an imagined tonal ideal is the beginning of a focal musical journey that should be patient, persistent and perpetual. (It includes the nurturance of free flowing relaxed “weeping willow” arms, supple wrists, and gently curved hands/fingers.)

Unfortunately, beginners of diverse ages, grab and squeeze notes in their earnestness to land the RIGHT ONES. And where children are concerned, who are immersed in the current public education system, being RIGHT is more often rewarded than delving deeper into a zone of creativity and expression that is abstract and intangible.

An applauding classroom of listeners will reinforce with approval, a piece played or even pounded out note perfect, although it lacks color, shape, expression and engagement. Perhaps the listeners’ consciousness has not yet been awakened which results in a mutual oblivion to aesthetic possibilities.

Regardless of the performance milieu, the beginning student faces common specific learning challenges:

NOTE READING

Given most of popular method books abounding, the piano teacher and student are confronted with a dearth of holistic approaches to piano learning.

In truth, most of the hot-selling, mainstream method books offer quick gratification five-finger pieces, (after a short stint with two and three-black key experiences) And even if the white note pieces are transposed from artificially constructed, “C Position” to “G Position,” they come with a built-in set of crutches. The student will fill in any missing finger numbers on the printed page, and might even write in the letter names he has learned from among seven in the alphabet. Each time he plays the piece, he relies on the finger numbers or inserted letter names, though finger number retention seems easier. (Manipulations of the alphabet that require reversals of letter names, when notes descend can be tricky, especially minus the BLACK INK reinforced reminders.)

I personally reject materials permeated with five-finger pablum. Instead I embrace Pre-notational symbols that are best absorbed and synthesized in baby steps with touch/tone sensitivity. And I embrace the floating, staff-less notes that show movement up and down or on the same level for repetition, while my singing voice prompts the student to join me with phrase sensitivity. We add Hand Signals to reflect melodic movement in space that’s borrowed from the teachings of Kodaly.

The black note experiences, incidentally, can be prolonged, and not inserted briefly as a form of anti-discrimination tokenism.

https://arioso7.wordpress.com/2012/02/23/bias-against-black-notes-stopped-me-in-my-tracks-video/

These twin or triple black key phrases don’t leave the child or beginning adult saddled with more than they can handle in early stage learning.

COMPOSING is a nice adjunct to Note name LEARNING and READING.

What better way to assimilate note names, movement in space, and meter, than for a student to create his own piece at each learning juncture.

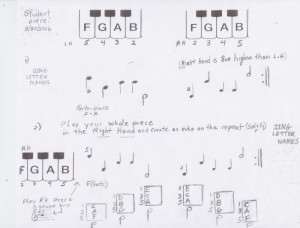

Case in point, “Liz,” age 8, composed two pieces that included two groupings of notes that required an echo on the repeat. Her initial composition was framed in 3 using quarters and half notes at her discretion. Her second, most recent composing experience, was based on learning to play a sequence of whole tones, hand over hand, F,G, A, B, that provided a “watery” atmospheric. (It invited submergence with sustain pedal which was enticement enough to encourage daily practicing.)

The student notated her own piece with stem up and down quarters and half notes of which she had considerable book exposure, and I expanded upon it for the upcoming lesson. Tomorrow I will attach one chord per phrase in graduated steps through the morsel’s development, not using three different chords that I’d inserted in my playing and on paper. The child will continue to practice a relaxed physical relationship to the keys with supple wrists, that will be reinforced at each lesson. She, like others, need continuous work on the synthesis of touch and tone that’s not an overnight accomplishment.

(My notation of the pupil’s piece does not include inserting letter names or finger numbers in the direct score except for the starting finger, though there’s a map of the three-black keys and their relation to white notes.)

In playing through the short phrase, musical rhythm counting is encouraged by singing, and the same will ensue with LETTER NAMES, absent inked in CRUTCHES within the score.

Frances Clark’s Time to Begin, delays use of the complete GRAND STAFF, as it feeds the floating staff-less notes for a considerable time using the black keys, but it simultaneously offers opportunities to identify white notes in relation to blacks by suggesting composing activities.

(In the realm of composing, a child or adult is motivated to create a collection of their pieces and even illustrate them. In 1985 I published an album of students compositions that included my added teacher accompaniment so that omposing became a mutually satisfying adventure.)

***

As far as published piano methods are concerned, none is perfect, in my opinion, with pitfalls abounding, but the fact that Clark resists the five-finger exposure ad nausea, and introduces the STAFF in an attenuated form with a line to space fragment of the whole, is laudatory.

In the course of Clark’s inspired Music Tree series, that integrates words and music, different fingers are assigned to notes that are related to LANDMARKS: Treble G, Middle C, Bass F, etc. which I find to be pedagogically sound, though sooner than later, my beginning student will be exposed to repertoire-based learning as a substitute for Method Book addiction of any kind.

Early MEMORIZATION

Adults and children alike will memorize parts of their pieces while learning them, so they lose their place as eyes veer from the score to hands, or to another fleeting internal or external cosmos. I discourage the dualism of memorization and note reading-in-progress, by focusing attention on the touch/feel/attentive listening triad of music absorption, with eyes riveted to the score. The transfer of visual note movement on the staff to relaxed arms, wrists, hands, and fingers, draped naturally over the keys, reinforces note reading, synthesized with musical expression.

The eventual mastery of a piece leading to memorization should ideally have an analytical foundation where beginning students find patterns, sequences, repetitions, within a composition that support its retention as it ripens over time.

Recommended examples of early pedagogy:

Irina Morozova teaching a 6 year old

Irina Gorin teaching a transfer student

Liz has first piano lesson, Part 2

from Arioso7's Blog (Shirley Kirsten)

https://arioso7.wordpress.com/2016/04/05/the-earliest-steps-in-piano-learning/

No comments:

Post a Comment